Family Portraits

In ancient epics, the poets use phrases such as 'a forest of spears,' saying one thing to imply much more. For each spear implies a warrior, the forest an army. With the army drawn up, a battle is imminent, and beyond or before the battle lies a history soaked in blood. In each fragmentary image we glimpse a whole, and from the narrow 'bank and shoal' of the present, as Shakespeare put it, we view the vast ocean of time.

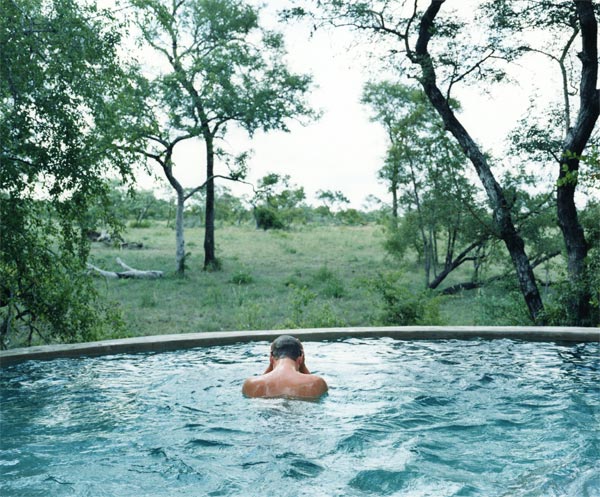

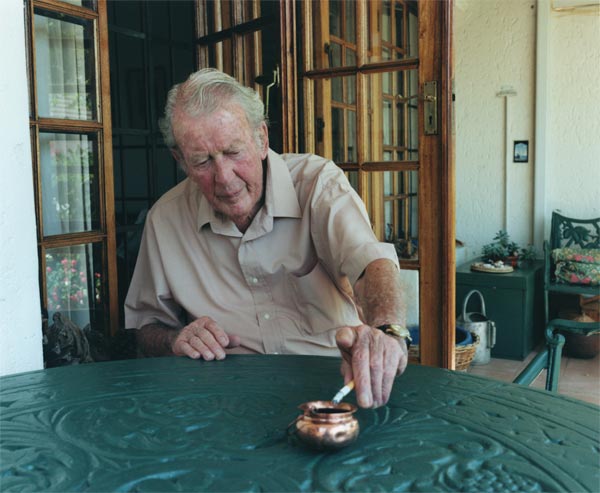

In Stuart O'Sullivan's domestic epic of South Africa, each image works this way, poetically, concisely. Behind and beyond what he reveals of an idyllic South Africa, of its sun-drenched lawns, pristine beaches and quiet living rooms, lies everything we can't see. The anger, hope, violence, and possibility of South Africa are, for the most part, excluded from the frame but more intensely present by implication. In a divided country still struggling to become whole, is it possible for any image not to have a double sense, a shadow? Is it possible for any word not to be ironic, any phrase not to be a figure of speech? Barbed wire curls along a garden wall, dividing Eden from a fallen world, but which is which? A mosquito net conceals a tea service like a shroud. In a framed photograph standing amidst the books on a bookshelf, a fire rages, burning down a house and a world that was. And everywhere people stand transfixed by the landscape, lost in thought, looking out toward everything we cannot see and the future they cannot fully anticipate.

O'Sullivan's friends and family, the subjects of these photographs, suggest a larger whole, not just the millions of other white South Africans but all their countrymen, the 'forest of spears.' The images give us glimpses of a South Africa seldom seen, a place elsewhere, but their real interest lies in their constant reiteration of the South Africa taking shape now. The narrative is carefully constructed to tell this inferential epic, weaving the strands of black and white. Early on, one of the photographs depicts an embrace between O'Sullivan's aunt and the woman who works with her at the AIDS N.G.O O'Sullivan's aunt directs. The occasion is a wedding in the townships outside Cape Town. The entire book is a comment on that embrace, and it echoes the title in its dream of a better place. It is especially poignant in that the work these women are doing represents the next great struggle in South Africa. This is a book of deep affection and little nostalgia, of offhand intimacy and graceful formality.

Unlike most translations of photography into book form, How Beautiful This Place Can Be should not be read as a collection of images selected from a disparate ouvre and sequenced after the fact. It is composed as a novel in pictures, a novel that has taken a decade to 'write.' As striking and memorable as many of the individual images are, they are not meant to stand on their own. Characters and places recur, water is a central motif, and, from the opening image, color weaves a dense fabric of associations. Colors connect, implicate, suggest, and even foreshadow. We routinely expect this of poets, less routinely of novelists, almost never of photographers.

O'Sullivan's project shares the idea of narrative integrity with several other recent book projects, especially Mitch Epstein's Family Business and Sally Mann's What Remains. All three attempt to sum up the contingent, enduring nature of family and place. Indeed, these artists are obsessed by place as the originating context for individuals, families, and societies, and the sense of place gives these narratives their extraordinary density. In a distinctly postmodern time, when all places are the same media-saturated place and identity is treated as a fiction or an off-the-shelf commodity, these artists harken to the call of being, as Heidegger put it, situating individual consciousness, grounding it, and taking full inventory of its contents. In this regard the photographers seem more both more responsible and more ambitious than most of their novelist contemporaries.

At the same time, O'Sullivan is fully aware of forces in and around photography that have qualified its practice. We can sense in his work the same distrust of formalism and personal expressiveness that animates the work of William Eggleston, Stephen Shore, and Thomas Struth, among others. This might be called a belief in the extraordinary subtlety of ordinary things, of letting the world speak for itself. The photographer says, Don't see me, see what I see, and only that way will you see me at all. And in spite of the book's careful orchestration, it is ultimately open-ended, as all family sagas must be. Its story can come to an end only with the exit of the author-photographer, not with the turning of a page.

Perhaps not even then. For the land remains, inexhaustible and sanctifying for both black and white, and the struggle to reconcile these histories, with their parallel burden of tragedy and expectation, goes on.

Lyle Rexer

Brooklyn, New York

About Stuart O'Sullivan

Stuart O'Sullivan was born in Johannesburg, South Africa in 1971. From 1990 to 1992, he studied Graphic Design in Cape Town and in 1993 moved to New York to study at the International Center of Photography. His first book, How Beautiful This Place Can Be was published by Nazraeli Press in 2004. He is represented by Daniel Cooney Fine Art in New York, where he resides. His fine art and commercial work is widely published, exhibited and collected.